Criminals can build Web dossiers with data collected by browsers

Everybody knows by now that websites collect information about users’ location, visited pages, and other data that can help them improve or monetize the experience.

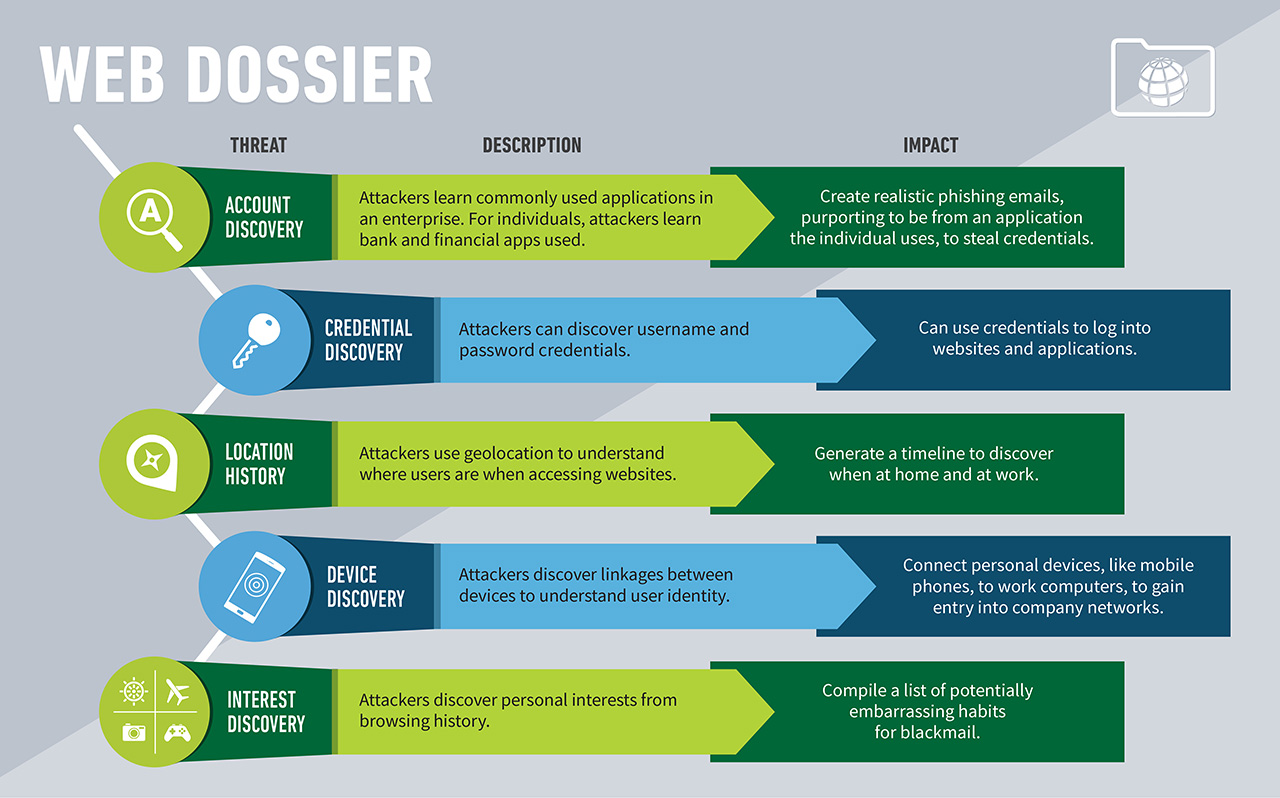

But just a small minority of Internet users realizes that browsers also collect/store information that can help attackers compile a “Web dossier” to be used for future attacks.

“An attacker could compile a list of applications you commonly log into from your URL history, including work applications and personal finance sites. Criminals can learn who in a company has access to the financial or payroll application, for example, and compile a list of usernames to use to break in. Knowing what applications are in use at a company can help an attacker craft more convincing phishing emails to try and trick users into exposing their passwords, which the attacker could then harvest,” explains Ryan Benson, a threat researcher at Exabeam.

By accessing users’ URL history, an attacker can learn about their personal interests, and use that information to guess their passwords or blackmail them (if the interest is controversial or illegal). Also, usernames and passwords saved in the browser’s password manager can be extracted and used to compromise a wide variety of accounts.

What kind of information does your browser store?

Exabeam’s researchers have performed two tests:

- One with Firefox and OpenWPM, a privacy measurement framework built on Firefox. They visited the 1000 most popular sites on the Internet without logging in, just navigating to three links on each of the websites

- A second on with Chrome. They visited a subset of popular sites (Google Search, Drive, and Mail; YouTube; Facebook; Reddit; Yahoo; Amazon; Twitter; Microsoft’s Outlook and OneDrive; Instagram; Netflix; LinkedIn; Apple; Whatsapp; Paypal; Github; Dropbox; the IRS site) and created accounts, logged in, and performed a relevant action.

In the first test, they found that 56 websites stored some level of geolocation information (via cookies) about the user on their local system, and 57 recorded a user’s IP address.

In the second test, they found that much potentially sensitive information is stored by popular services into the browser: account usernames, associated email addresses, search terms, titles of viewed emails and documents, downloaded files, viewed products, names, physical addresses, and more. And, if the in-browser password manager is on, sensitive credentials are stored and can be accessed by crooks that manage to compromise your computer.

“Creating malware to harvest information stored in a browser is quite straightforward, and variants have been around for years, including the Cerber, Kriptovor, and CryptXXX ransomware families,” Benson noted.

“The free NirSoft tool WebBrowserPassView dumps saved passwords from Internet Explorer, Mozilla Firefox, Google Chrome, Safari, and Opera. While ostensibly designed to help users recover their own passwords, it can be put to nefarious use.”

Collecting this data is especially easy to do on shared computers. “If a machine is unlocked, extracting browser data for analysis could be done in seconds with the insertion of a USB drive running specialized software or click of a web link to insert malware,” he says.

Once collected, all this data can be used to map a user’s work hours, habits, interests, locations, online use and accounts, the type of devices he or she uses, and so on.

Preventing data collection

All this information is collected via things like browsing history and bookmarks, HTTP and HTML5 cookies, saved login info (via in-browser password managers, and via the autofill option.

Web browsers also temporarily store parts of web pages – images, JavaScript code, HTML files, and more – in the browser cache. “Cached items often expire and are deleted relatively quickly, but are rich sources of information while they last,” Benson added.

For those users who would prefer browsers not to store this information, there are many options, but each has some cons.

For example, disabling HTTP cookies means that many websites will have issues, especially if a user needs to log in. Disabling Autofill means you’ll need to retype common information on websites over and over again. Using a 3rd-party password manager is good, but there is no guarantee that that software doesn’t have vulnerabilities and, if it’s cloud-based, you are still sending password information off to a 3rd-party and trusting that it is secure and confidential.

In general, the best option is to browse in “Incognito mode.” This means that there are little to no local artifacts saved from a session for local attackers to exploit, but you’ll also get no site customization or saved logins.