Turning plain language into firewall rules

Firewall rules often begin as a sentence in someone’s head. A team needs access to an application. A service needs to be blocked after hours. Translating those ideas into vendor specific firewall syntax usually involves detailed knowledge of zones, objects, ports, and rule order. New research from New York University examines a different starting point, one that treats natural language as the entry point for firewall configuration.

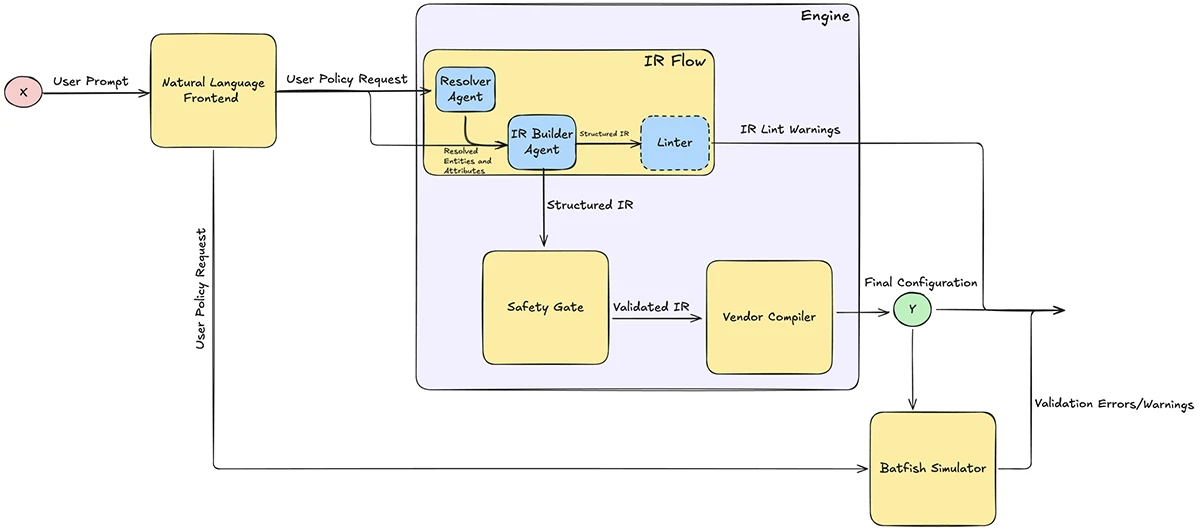

The paper presents a prototype system that accepts policy requests written in everyday language and converts them into structured firewall rules. The work explores how language models can assist with intent parsing while keeping configuration, validation, and enforcement under deterministic control.

Proposed system architecture

That design choice resonates with practitioners who manage firewalls at scale. Dhiraj Sehgal, Senior Director of Platform Security at Versa Networks, told Help Net Security that natural language interfaces deliver the most value when they align with how enterprise firewalls are operated day to day. He noted that the paper deliberately limits the language model to extracting intent and leaves validation, compilation, and enforcement to deterministic systems. According to Sehgal, that mirrors operational environments where traceability, review, and controlled change take priority over automation driven purely by speed.

From written intent to structured policy

The research focuses on the gap between how administrators describe security policy and how firewalls consume it. In many organizations, the initial policy discussion happens in plain text, tickets, or chat messages. The translation step into firewall rules introduces risk through misinterpretation or omission.

The proposed system begins with a natural language interface. An administrator submits a request such as allowing a department to reach a SaaS service over HTTPS during business hours. The system processes that text and extracts key elements including sources, destinations, protocols, actions, zones, and time constraints.

Large language models support this step by identifying entities and resolving ambiguous terms. The model output follows a strict schema. The language model produces structured data rather than free text, which keeps its role bounded and predictable.

Sehgal pointed to Google’s BeyondCorp program as a well documented example of intent driven network policy. He explained that during Google’s move away from perimeter based trust, engineers focused on validating observed traffic against declared intent. Unexpected behavior surfaced through telemetry analysis, followed by formal policy updates, which reinforced the value of evidence guided change rather than silent rule modification.

The role of an intermediate representation

A central feature of the design is an intermediate representation that captures firewall policy intent in a vendor agnostic format. This representation resembles a normalized rule record that includes the five tuple plus additional metadata such as direction, logging, and scheduling.

This layer separates intent from device syntax. Security teams can review the intermediate representation directly, since it reflects the policy request in structured form. Each field remains explicit and machine checkable.

After the intermediate representation is built, the rest of the pipeline operates through deterministic logic. The current prototype includes a compiler that translates the representation into Palo Alto PAN OS command line configuration. The design supports additional firewall platforms through separate back end modules.

In operational settings, Sehgal described policy intent as largely stable once it is authored. A rule written in natural language is validated offline and deployed through standard change control. Runtime telemetry then shows how traffic behaves in practice. When an unexpected system appears after a migration, logs and metrics highlight the deviation. Teams confirm intent with application owners and submit a narrowly scoped update through the same review process.

Validation embedded in the workflow

The system applies multiple validation steps before producing vendor specific output. A general linter examines the intermediate representation for structural issues such as missing fields, invalid port ranges, or duplicate identifiers. This step focuses on schema integrity.

A vendor specific linter applies rules tied to the target firewall platform. In the prototype, this includes checks related to PAN OS constraints, zone usage, and service definitions. These checks surface warnings that operators can review.

A separate safety gate enforces high level security constraints. This component evaluates whether a policy meets baseline expectations such as defined sources, destinations, zones, and protocols. Policies that fail these checks stop at this stage.

After compilation, the system runs the generated configuration through a Batfish based simulator. The simulator validates syntax and object references against a synthetic device model. Results appear as warnings and errors for inspection.

Sehgal noted that enforcement can still adapt temporarily through predefined controls such as rate limits, based on observed behavior, without changing the underlying policy. This preserves audit trails and intent fidelity, even if response times rely on human review.

Testing in synthetic environments

The evaluation relies on synthetic network contexts that describe address objects, zones, and services. Each test case includes a natural language request, an expected intermediate representation, and an expected firewall configuration.

The researchers measure two outcomes. One checks whether the language driven components produce the correct structured policy. The other checks whether the compiler emits the expected command line configuration.

Across the test set, the system achieves a success rate of roughly 85 percent. Errors typically arise from ambiguous phrasing or edge cases in platform syntax. The paper treats these results as evidence that schema bound language processing combined with deterministic compilation can support firewall rule generation in controlled settings.

Operational considerations and limits

The paper also discusses practical constraints. Natural language requests often omit details such as zones or precise object names. Accurate results depend on a well maintained catalog of network objects and services.

Rob Rodriguez, Senior Director of Global Field Engineering at FireMon, said the quality of that underlying environment plays a central role in whether natural language driven policy creation succeeds. In large enterprises, object catalogs often contain legacy address groups, reused zones, and SaaS definitions that have drifted over time.

Rodriguez said a practical safeguard is to treat object hygiene as a gating condition before intent based rule generation begins. He described approaches where automated checks flag stale, unused, or overlapping objects and require cleanup or explicit confirmation before a rule moves forward. Some teams also require that any object referenced by a generated rule already shows active usage or passes a recent validation window, otherwise the request pauses for human review.

Differences between firewall platforms add complexity. Application aware rules on one platform may translate into port based rules on another. The compiler handles these cases through conservative mappings or diagnostics that inform the operator.

Rodriguez also highlighted the role of pre deployment simulation that goes beyond syntax checks. Even when a rule is structurally valid, reachability and change impact analysis can show which new paths the rule opens compared to the existing state. This type of analysis helps teams understand policy effect before deployment and supports informed approval decisions.

For long term lifecycle management, Sehgal described common operational practices such as scheduled reviews of rules with no traffic over periods like 60 or 90 days. Analytics can identify candidates for cleanup, after which teams decide whether to retire, consolidate, or narrow scope based on observed behavior and business relevance.

Rodriguez added that some of the most dangerous firewall rules are context sensitive rather than generically unsafe. Policy decisions often depend on business function, regulatory exposure, or timing. Mature teams address this by layering business metadata and risk scoring into policy workflows. Rules that touch regulated assets, critical applications, or exposed zones trigger stricter approval paths and narrower defaults. Over time, this creates feedback where firewall policy reflects operational reality and business priorities. Rodriguez said the safest implementations make the balance between response speed and certainty explicit through process and review.

A cautious approach to automation

This research reflects a broader trend toward applying language models to infrastructure tasks under strict control. The system treats the language model as an assistive component that proposes structured intent. Validation, compilation, and enforcement remain deterministic.

Sehgal said the paper’s focus on constrained generation, layered checks, and offline simulation aligns with how firewall teams already operate. Natural language speeds up intent expression, while telemetry, structured review, and human judgment continue to guide secure policy evolution.

The work positions itself as an early step toward more accessible policy management. Future directions include broader vendor support, reachability analysis, and studies involving practicing administrators. The core idea centers on aligning how people describe security policy with how firewalls consume it, using structure and validation as the bridge.