Formal proofs expose long standing cracks in DNSSEC

DNSSEC is meant to stop attackers from tampering with DNS answers. It signs records so resolvers can verify that data is authentic and unchanged. Many security teams assume that if DNSSEC validation passes, the answer can be trusted. New academic research suggests that assumption deserves closer scrutiny.

Researchers from Palo Alto Networks, Purdue University, the University of California Irvine, and the University of Texas at Dallas present an analysis of DNSSEC that goes beyond bug hunting. Instead of searching for individual flaws, the team built a mathematical model of the protocol and asked a deeper question. Does DNSSEC, as written and deployed, always behave securely under all conditions?

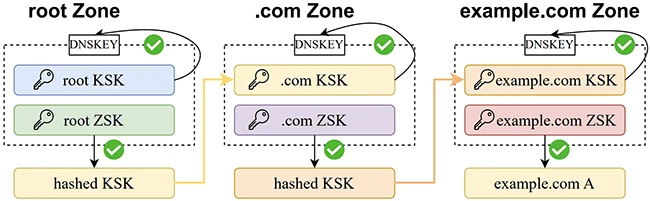

The chain of trust in DNSSEC: For a zone, the KSK is used to verify the DNSKEY pair (KSK and ZSK), while the ZSK is used to verify the child zone’s KSK or A records.

A different way to test DNSSEC

The research introduces a framework called DNSSECVerif. It uses formal verification techniques that are common in cryptographic protocol analysis but rarely applied to DNSSEC at this scale. The model captures how resolvers, authoritative servers, and caches interact, including cryptographic checks and concurrent queries.

DNSSEC has grown through incremental fixes. Each change addressed a known problem, but the protocol as a whole was never proven sound. Formal verification forces every assumption to be explicit, including how caches behave and how records interact across zones.

The team used this approach to prove four core security properties that DNSSEC aims to provide. These include data origin authentication, data integrity, correct chain of trust validation, and authenticated denial of existence. Proving these properties required modeling resolver caches in detail, since caching errors can undermine validation even when signatures are correct.

When standards collide

The most significant finding comes from how DNSSEC standards interact. DNSSEC supports two mechanisms for proving that a domain name does not exist: NSEC and NSEC3. Many zones use only one of them, but the standards do not forbid mixing both in the same zone.

The researchers found that this coexistence creates an authentication gap. NSEC relies on ordered domain names, while NSEC3 relies on hashed names. When both appear together, a resolver can be tricked into accepting a denial of existence that skips over valid domains.

Formal analysis showed that a resolver can accept a valid looking NSEC3 proof while ignoring an NSEC record that contradicts it. This is not a coding bug. It follows directly from how the standards define validation rules.

Evidence from live resolvers

To test whether this mattered outside theory, the researchers examined real implementations. They tested mainstream DNS software, including BIND, Unbound, PowerDNS, Knot, and Technitium. Every resolver tested cached misleading NSEC3 denial records in mixed mode zones.

None of the resolvers immediately returned incorrect answers in their tests. However, polluted caches mean future queries can be influenced by contradictory data. This creates conditions for denial of service and persistent confusion inside the resolver.

The team then ran an internet wide measurement study of more than 2.2 million open resolvers. Many of these resolvers accepted both NSEC and NSEC3 responses. Compared to standard DNS queries, NSEC and NSEC3 queries produced a much higher rate of SERVFAIL responses and timeouts. These failures consume extra resolver resources and can amplify attack traffic.

Old attacks resurface

The formal model also rediscovered three known classes of DNSSEC attacks without being explicitly programmed to find them. One is NSEC based zone enumeration, where attackers list all domain names in a zone. Another is algorithm downgrade attacks, where weak or unsupported cryptographic algorithms allow validation to be bypassed.

A third involves DoS through unvalidated cache reuse. Some resolvers store both validated and unvalidated data in the same cache. An attacker can exploit troubleshooting features to inject records that later disrupt validation for other clients.

The fact that these attacks reappear in a formal model matters. It shows they stem from protocol design choices, not just implementation mistakes.

Implications for DNSSEC in production

DNSSEC correctness is not binary. Validation passing does not guarantee safety if the protocol rules themselves allow inconsistent states.

The authors recommend avoiding mixed NSEC and NSEC3 deployments entirely. They argue that standards bodies should treat this configuration as unsafe and require resolvers to fail validation when it appears.

They also suggest that formal verification should play a role earlier in protocol design. DNSSEC is widely deployed and difficult to change, which makes design flaws expensive to correct.