Apple privacy labels often don’t match what Chinese smart home apps do

Smart home devices in many homes collect audio, video, and location data. The apps that control those devices often focus on the account owner, even when the technology also captures guests, neighbors, and other people who never agreed to be monitored.

New research examined whether Chinese smart home apps provide privacy protections for these bystanders. The study reviewed 49 apps available in Apple’s App Store in mainland China and found consistent gaps in bystander privacy, along with frequent inconsistencies between privacy policies, in-app settings, and App Store privacy labels.

Smart home apps collect sensitive data at scale

The study found that all 49 apps required users to register with a mobile phone number and verify the account using an SMS code, reflecting China’s real-name registration system. In the iOS environment, most apps also offered third-party login options such as WeChat or Apple ID.

The researchers found broad data collection across the app ecosystem. Direct collection included information provided during registration, including phone numbers, plus optional profile information such as usernames and avatars. Indirect collection included device identifiers such as IMEI and MAC addresses, operating system versions, and network information. Many apps also collected location data, including Wi-Fi details, IP addresses, and base station information.

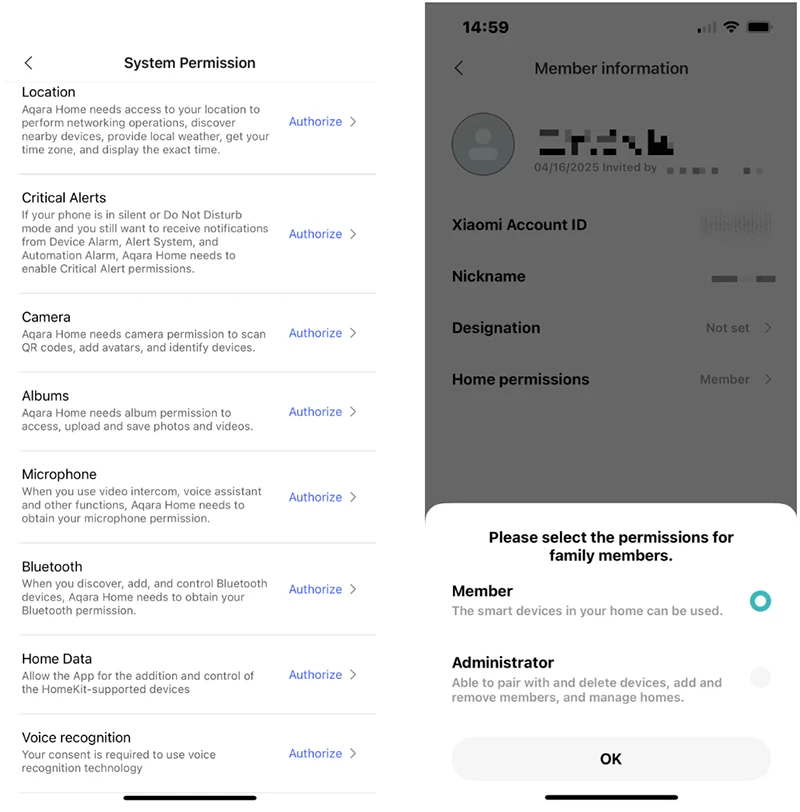

Most apps requested a common set of permissions, including access to location services, the camera, the photo album, the microphone, contacts, Bluetooth, and system notifications. These permissions supported functions such as device pairing, device discovery, automation rules, media uploads, voice assistant features, and alerts.

The researchers also found widespread collection of sensitive personal information disclosed in privacy policies. Thirty-nine of the 49 apps reported collecting financial information such as payment amounts, bank card details, or third-party payment account data. Privacy policies across all apps stated they collected biometric information, including facial recognition data. Some apps also reported collecting health-related data such as blood pressure, blood sugar levels, menstrual cycle data, heart rate, sleep patterns, weight, and movement activity.

The paper notes that these apps and connected devices may collect data about bystanders, such as visitors or passersby captured through cameras or microphones. The researchers found that none of the apps explicitly disclosed how sensitive personal information related to bystanders was handled.

Bystander privacy is largely absent

The study divided bystanders into three categories: live-in bystanders, visiting bystanders, and uninvolved bystanders such as neighbors or passersby. Across the tested apps, privacy controls were designed around the primary account holder.

Some apps supported device sharing with other users, typically family members in the same household. Nineteen of the 49 privacy policies described mechanisms for users to share data or device access with other users. Several apps supported invitations through third-party platforms such as WeChat. The policies generally did not describe how consent should be obtained from secondary users or how their data would be managed independently.

For visiting and uninvolved bystanders, the researchers found no explicit mentions or user interface features across the app sample. The traceability results classified bystander privacy protections for these groups as absent across all 49 apps.

The researchers also found that bystanders received no notification or consent mechanisms during account creation, permission requests, or deletion workflows. Privacy management depended on the primary user’s account.

Examples of app system permissions and controls (Source: Research paper)

Privacy policies and app interfaces often diverge

The study included a traceability analysis that mapped privacy policy statements against observed UX and UI behavior across four areas: data collection, data sharing, data control and management, and security measures.

In many areas, the researchers found consistency between privacy policy disclosures and user interface behavior. Device identifier collection, location data collection, multimedia permissions, and logging were generally disclosed in policies and implemented through system permission requests and settings.

The study also identified recurring mismatches. For example, all apps referenced legal requirements to share data with law enforcement or public security authorities, and the traceability analysis classified every app as “broken” in this category because none offered UI features that would notify users about this type of data sharing.

The researchers also found inconsistencies in user control over marketing and personalization. Twenty-eight apps provided controls for personalized or marketing content that aligned with their privacy policies. Four apps described such controls in their policies without providing corresponding settings in the interface.

The researchers also documented usability problems related to deletion workflows. Some apps used confusing or repetitive deletion and consent-revocation options, and others applied deletion rules inconsistently depending on user role. One example cited in the paper showed connected devices remaining active even after account deletion.

Government access provisions limit deletion guarantees

The study found that deletion rights described in privacy policies were often constrained by mandatory cooperation requirements tied to China’s Cybersecurity Law. The paper describes provisions across all 49 apps stating that companies must provide technical support and assistance to public security and national security authorities when required.

The researchers describe this as a structural issue in the Chinese smart home ecosystem, where privacy policies include deletion mechanisms for users while also reserving broad authority-driven access to personal data under national security and public interest provisions.

The paper includes an example in which a township-linked version of an app stored residents’ video feeds indefinitely on jointly operated servers and restricted deletion without official approval.

Apple privacy labels often conflict with policy and UI evidence

The researchers also reviewed Apple App Store privacy labels for the 49 apps and compared them against privacy policies and observed UX and UI behavior. The study found widespread inconsistencies and underreporting.

Twenty-six apps claimed in their privacy labels that they did not collect any data used to track users. Their privacy policies disclosed third-party SDK usage for monitoring and analytics.

The study also found that 23 apps claimed in their App Store labels that they did not collect any data linked to the user, despite requiring phone-number-based account registration.

Six apps declared in their privacy labels that they collected no data at all. The researchers found that their privacy policies disclosed data collection practices and third-party SDK sharing, creating a mismatch between labels and the written policy disclosures.

The researchers recommended stronger bystander-focused privacy controls, improved transparency in app privacy interfaces, and stronger consistency between App Store privacy labels and observed data practices.