Android VPN apps used by millions are covertly connected AND insecure

Three families of Android VPN apps, with a combined 700 million-plus Google Play downloads, are secretly linked, according to a group of researchers from Arizona State University and Citizen Lab.

Finding the secret links

Virtual private networks (VPNs) are widely marketed as tools for enhancing privacy, securing internet traffic, and shielding users from surveillance.

Unfortunately, the consumer VPN ecosystem is decidedly opaque, making it difficult (and sometime impossible) for users to make an evidence-based decision that will allow them to achieve those goals.

Researchers Benjamin Mixon-Baca, Jeffrey Knockel and Jedidiah R. Crandall have decided to analyze some of the most downloaded Android VPN apps and focused on Singapore-based providers “because of the previous research that observed deceptive providers incorporating in Singapore.”

They collected information about the providers from their websites, Google Play pages, business filings, social media accounts and posts, and did a static and dynamic analysis of their APKs.

“We analyzed each for security issues, finding that, in addition to sharing other code similarity features, each family of apps also shared problematic security properties. These shared flaws themselves serve as a signature by which to map relationships between providers,” the researchers explained.

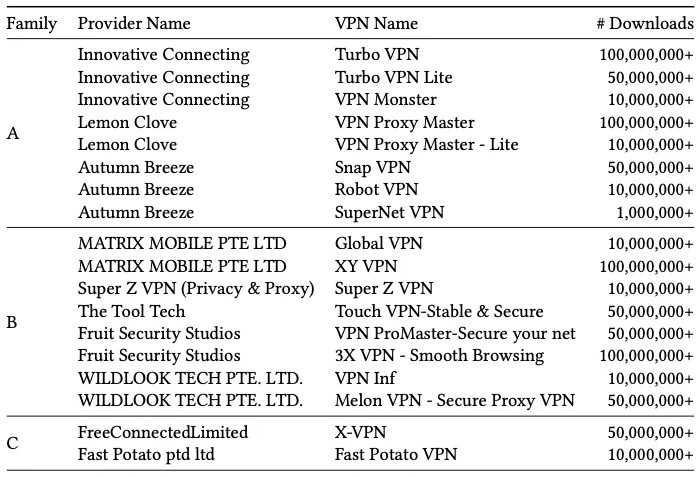

They identified three distinct families of VPN providers with hidden “links” and shared flaws:

The covertly connected apps and the number of Google Play Store downloads for each (Source: The researchers’ public paper)

The eight apps in Group A, offered by three providers, share nearly identical Java code, libraries, and assets; support IPsec and Shadowsocks (by using the same libraries); share characteristic files; and share security flaws:

- They collect location-related data (even though their privacy policies say they don’t)

- Use weak/deprecated encryption

- Contain hard-coded Shadowsocks passwords which, if extracted, may allow attackers to decrypt user traffic. These hard-coded credentials work across different apps and servers, proving that these providers use the same backend infrastructure.

The eight apps in Group B, ostensibly developed by five distinct providers, support only the Shadowsocks protocol (by using the same libraries to do it), some reach out to the same Shadowsocks service, use the same defense mechanisms, and also use the same hard-coded password to connect to Shadowsocks servers (on different ports). “All of Family B’s VPN servers are hosted by a single company, GlobalTeleHost Corp,” the researchers noted.

Group C consists of two providers that distribute one mobile VPN app each. They both use a custom tunneling protocol; have “structurally and functionally similar” source code; implement the same obfuscation and anti-reverse engineering countermeasures; and are susceptible to connection inference attacks using the client-side blind in/on-path attacks.

The researchers also found that the providers of three of the 21 applications they analyzed “appear to have no links to other VPNs.”

The danger for users

“The undisclosed location collection issue is a major violation of user trust and privacy given the provider explicitly stated they did not collect such information,” the researchers pointed out.

“The client-side blind in/on-path attacks allow an attacker to infer with whom a VPN client is communicating. Most critically, on many of the VPNs we analyzed, a network eavesdropper between the VPN client and VPN server can use the hard-coded Shadowsocks password to decrypt all communications for all clients using the apps. These weaknesses nullify the privacy and security guarantees the providers claim to offer.”

But what should be even more concerning, they say, is the fact that “the providers appear to be owned and operated by a Chinese company [i.e., Qihoo 360] and have gone to great lengths to hide this fact from their 700+ million combined user bases.”

The reasons for creating this illusion of choice are hard to determine. The researchers speculate that the company possibly wanted to contain any reputational damage that may arise to a single provider, while maintaining costs low and management easy.

Earlier this year, the Tech Transparency Project (TTP) has also unearthed the link between Qihoo 360 – a company with connections to the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) – and many free VPN apps offered for download in Apple’s App Store.

“Ultimately, TTP determined that 20 of the top 100 free VPN apps in the App Store were owned by companies or individuals based in mainland China or Hong Kong but did not clearly disclose their China ties,” the initiative stated.

“[VPN apps] can (…) pose serious risks because the companies that provide them can read all the internet traffic routed through them. That risk is compounded in the case of Chinese apps, given China’s strict laws that can force companies in that country to secretly share access to their users’ data with the government.”

UPDATE (August 29, 2025, 02:30 p.m. ET):

This article has been amended to clarify that not all of the VPN apps that were analyzed are from providers that intentionally disguise their ownership, and that the researchers did not discover hidden ties between all of the analyzed apps.

Subscribe to our breaking news e-mail alert to never miss out on the latest breaches, vulnerabilities and cybersecurity threats. Subscribe here!