What keeps phishing training from fading over time

When employees stop falling for phishing emails, it is rarely luck. A new study shows that steady, mandatory phishing training can cut risky behavior over time. After one year of continuous simulations and follow-up lessons, employees were half as likely to take the bait.

The research, carried out by teams from various universities, offers a look at how behavior changes when training never stops.

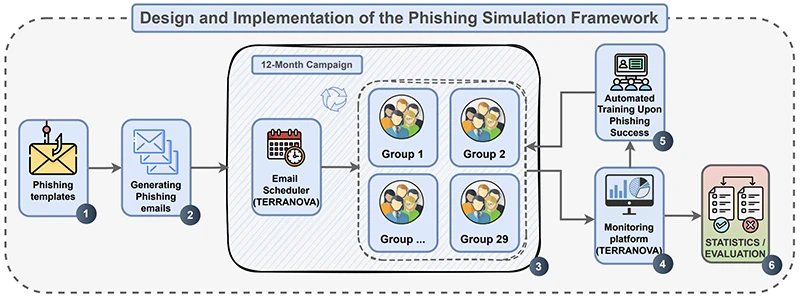

Overview of the research workflow, illustrating each stage from phishing email template design through the email campaign, data collection, trainings, and statistical analysis.

Why long-term training matters

Phishing still kicks off most cyberattacks, and awareness training is standard practice. Still, many companies wonder if it actually works. The study followed more than 1,300 employees across 20 companies over a 12-month period to find out what works when phishing simulations are repeated regularly and backed by mandatory training.

Each employee received a series of simulated phishing emails during the year. When someone took an unsafe action, such as clicking a malicious link, the system assigned a short mandatory training session before the person could return to work. More than 13,000 phishing emails were sent in total, each one designed to test different psychological cues such as urgency, curiosity, or helpfulness.

By the end of the experiment, employees were making far fewer mistakes. Unsafe clicks and submissions dropped by roughly half within six months and then stabilized near the industry average for organizations that use ongoing training. The findings suggest that repetition and timing matter more than the format of the lessons themselves.

Emotions still drive mistakes

The study also examined which emotional and contextual triggers made people most likely to engage with a phishing message. It found that some emotional cues continue to have an effect even in workplaces with regular awareness campaigns.

Emails that appealed to helpfulness or cooperation were the most successful at tricking users. Messages that seemed to come from within the organization also performed better than those appearing to come from an external source. When these two traits were combined with personalized details, the success rate rose noticeably.

By contrast, messages that relied on urgency or authority were less effective. The authors believe this may reflect growing familiarity with these tactics, which employees have seen repeatedly in both real attacks and training exercises. Fear and curiosity still played a role, but not as much as appeals to trust and altruism.

The results suggest that phishing tactics are shifting from obvious pressure tactics to more subtle social ones. Employees who want to be helpful or appear responsive can become easier targets than those reacting to fear or haste. For CISOs, this reinforces the need to teach users about manipulation through trust and cooperation, not just the warning signs of urgent or threatening messages.

Richard A. Dubniczky, a co-author of the study, told Help Net Security that the research also hinted at small differences between departments. “We did find some correlations in susceptibility,” he said. “For example employees working in HR, Finance, Legal professions were more likely to download and open dangerous attachments. This does not necessarily represent a worse security mindset on their part, it can be the result of them being much more accustomed to working with attachments. In contrast, developers were highly likely to click on emails that say that they were mentioned in a Jira ticket, click to find out why.”

He added that while these findings were interesting, the sample sizes for some departments were too small to draw strong scientific conclusions. Still, the observations highlight how role-specific habits can influence risk and how training might need to reflect those patterns.

Immediate feedback changes behavior

One of the most striking findings involves the timing of feedback. When employees clicked a phishing link and then received an immediate explanation and training prompt, they were far less likely to repeat the behavior. Around seven in ten employees who failed once did not do so again.

This pattern supports the idea that context and timing are as important as the content of training. When people see right away what they did wrong and how they were manipulated, the lesson sticks. Waiting for quarterly or annual awareness sessions may allow the memory of that moment to fade.

The researchers describe this as “just-in-time” training, where each learning event follows directly from a real interaction. They note that this approach helps awareness feel relevant to day-to-day work rather than a detached corporate exercise.

Keeping engagement from fading

Dubniczky said maintaining employee engagement over time is a major challenge for most organizations. “In contrast with other research in the area, a key contribution of ours was a mandatory training after each failed phishing attack,” he explained. “This strikes a good balance between not needlessly bothering careful employees with monthly or quarterly trainings while making sure that the highest risk individuals are constantly trained.”

He recommended that organizations vary their phishing simulations to keep users alert. “We’d recommend performing monthly penetration tests on smaller groups of people in diverse departments of the organization with a seemingly random pattern, and making re-training mandatory in case of successful attacks,” he said. “It’s also difficult to generalize on this, but this approach seems much more effective than periodic presentation-style trainings.”

What organizations can learn

The research also revealed how employee turnover affects awareness levels. When new hires joined the companies during onboarding periods, phishing success rates temporarily rose. Those employees accounted for a large share of mistakes until they completed the mandatory modules. This suggests that continuous programs need to include fast onboarding and consistent follow-up for new staff.

While the study focused on one European holding company and its subsidiaries, the researchers believe the results apply broadly to any environment where phishing testing and awareness programs are ongoing. They also acknowledge some limits. Because participants knew that simulations were part of company policy, they might have been more cautious than in a real attack. Still, the long observation period and the mix of different emotional cues make this work one of the most extensive in the field.

Open data for others to test

To support transparency, the team published its email templates, data, and code on GitHub. The repository includes the phishing messages used in the experiments and scripts for analyzing user behavior. This allows other organizations to study or adapt the materials for their own awareness programs.

eBook: Defending Identity Security the Moment It’s Threatened